In the fall of 2018, after visiting an art gallery and observing the amount of time people would spend in front of a piece of art, I became curious about why some people would pass by a piece, conveyor-belt style, while others would stand focused, patient, arms behind their back, and still others who would observe from the middle of the space and take everything in all at once. I wondered if any research had been done on the average length of time a person spends looking at art in a gallery.

According to New York Times writer Stephanie Rosenbloom, “the average visitor spends 15 to 30 seconds in front of a work of art….” I found another report that put the time at an average of twenty-two seconds.

While being interested in the length of time we engage art, I also started thinking about how to expand ideas of collage into sound. Paper and glue started to frustrate me because my process was often tedious and kept me from immediate expression. After weeks of digging around online and investigating sound experiments and noise machines, I walked into a Portland fixture for electronic music producers called Control Voltage in the Mississippi district.

Looking back on it makes me feel like a Johnny Daydreamer. I stood in front of two patient employees who listened to what I was awkwardly trying to articulate as if no one else had thought of collage and sound. They not only humored me, they understood what I was trying to do and directed me to the samplers. I walked out of the store that day with a Roland SP404A, a machine capable of sampling and playing back whatever sounds I put into it.

While doing the deep dive on getting the 404 to do what I wanted, I also continued to nurture the curiosity about engagement with art and how sound could be implemented in that twenty-two second window of time. I had many ideas but I also got carried away with sampling and layering sounds and I acquired two more samplers to noodle around with.

As of 2022, my initial interest in sound has expanded beyond experiments in sampling and into synths, drum machines, and guitar pedals. These gadgets combine to help me create in real time without obstructions like scissors, glue, or paper but I never stopped composing mixed-media pieces and recently found a way to combine the two.

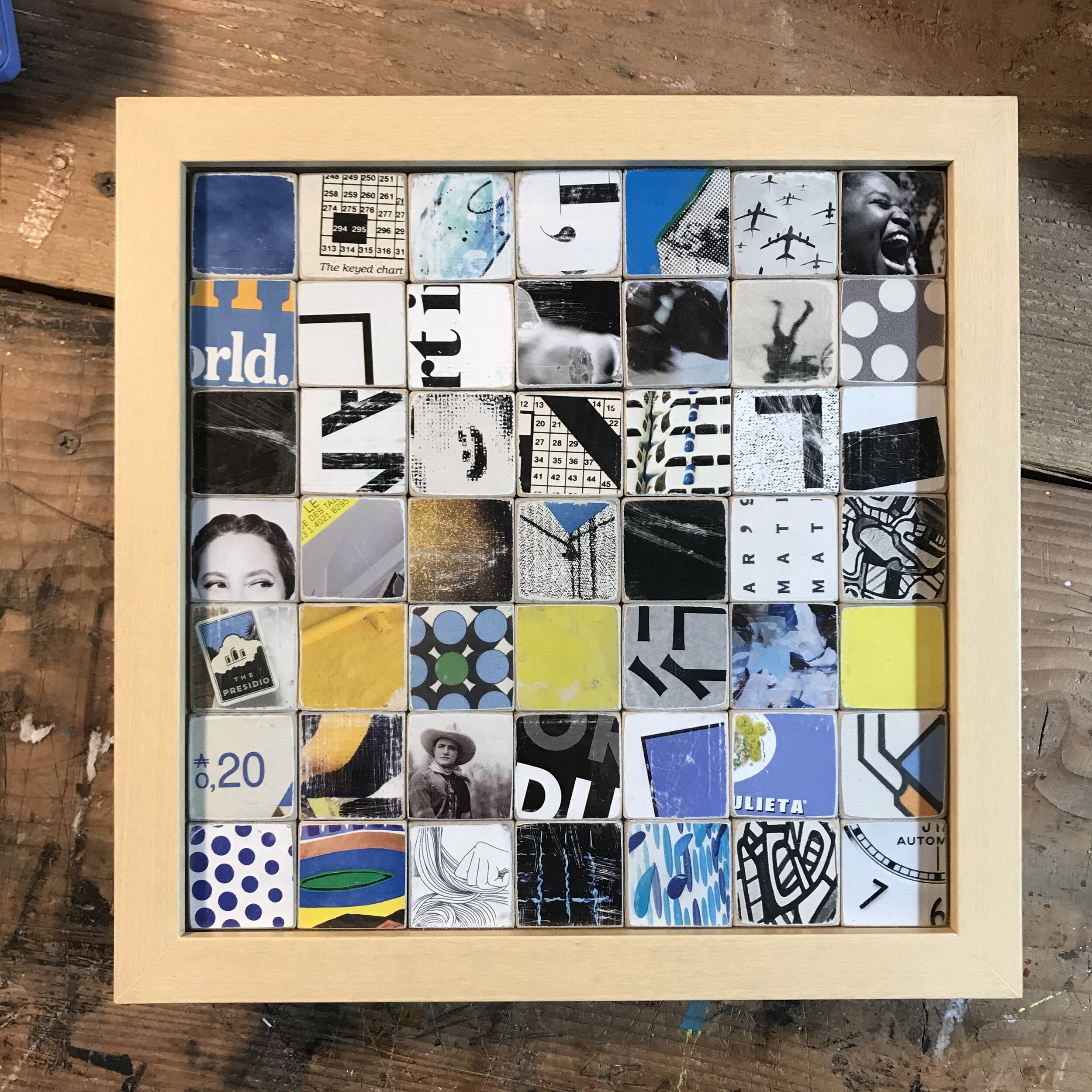

My new A/V Curio series is a fun way for me to continue to feed the original, but evolving interest in sight and sound and the tactile way we can engage with art. The series includes 999 completely original audio and visual compositions packaged in 333 miniature parcels. Each piece is a blend of handmade paper composition, photography, and embedded sound. One parcel contains three original numbered pieces. The A/V Curios ($13.00, shipping included) are available now in the store: http://jeremypeggdesigns.com/store/av-curio